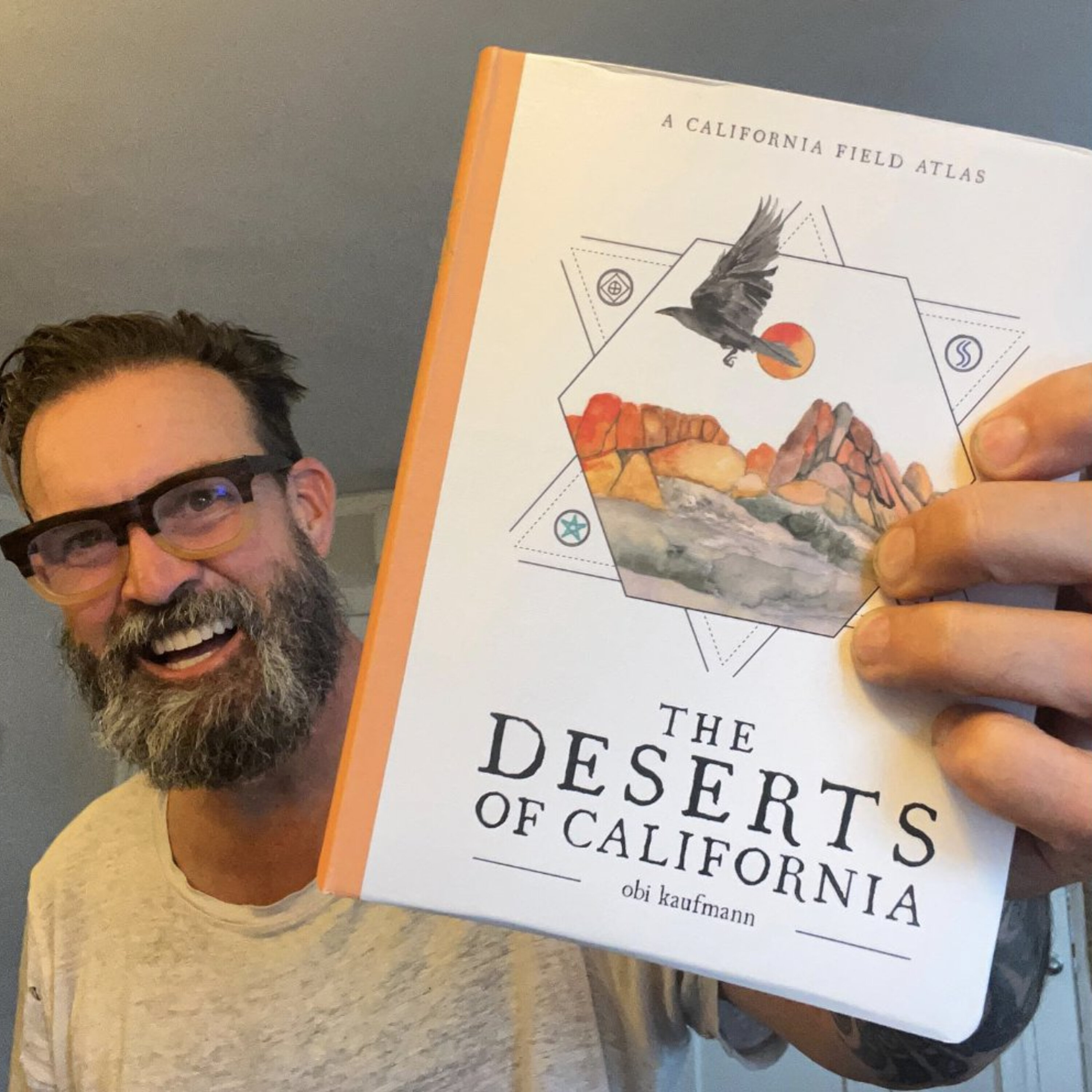

About The Guest(s): Obi Kaufmann is an artist, author, and naturalist known for his California Field Atlas series. His latest book, "The Deserts of California," explores the biodiversity and ecological systems of California's deserts.

Summary: Obi Kaufmann joins hosts Chris Clarke and Alicia Pike on the "90 Miles from Needles" podcast to discuss his latest book, "The Deserts of California." The book is part of his California Field Atlas series, which aims to explore the how of ecological systems rather than the what or where. Kaufmann shares his fascination with the complexity and diversity of California's deserts and the importance of celebrating and understanding their biodiversity. He also discusses the challenges of conservation and preservation in the face of development and exploitation. Kaufmann emphasizes the need for a democratic approach to finding solutions and the power of combining data and love in stewardship efforts. The conversation touches on the changing nature of the deserts, the importance of oral tradition and sharing knowledge, and the role of beauty and art in inspiring curiosity and hope.

Key Takeaways:

- The California Field Atlas series aims to explore the how of ecological systems rather than the what or where.

- The deserts of California are full of biodiversity and ecological complexity, challenging the perception of them as empty spaces.

- Conservation efforts require a combination of data, love, and understanding to address the challenges of development and exploitation.

- The deserts are a moving target, constantly changing and adapting to new conditions.

- The power of beauty and art lies in its ability to inspire curiosity and hope.

Obi Kaufmann's podcast with Greg Sarris, Place and Purpose, can be found here: https://www.placeandpurpose.live/

Order The Deserts of California here: https://bookshop.org/p/books/the-deserts-of-california-a-california-field-atlas/19407146?ean=9781597146180

Quotes:

- "The complexity is where the truth is. When things get too simple, too generalized, we miss so much." - Obi Kaufmann

- "The desert is doing so much heavy lifting for both of those goals [conservation and carbon zero]." - Obi Kaufmann

- "Democracy is having this conversation right now here." - Obi Kaufmann

- "The desert itself is an indicator landscape, if you will. It's a litmus test of our stewardship." - Obi Kaufmann

- "Acceptance of the natural cycles and patterns in nature brings peace and understanding." - Alicia Pike

- "The combination of data and love is a powerful force for conservation and preservation." - Obi Kaufmann

Become a desert defender!: https://90milesfromneedles.com/donate

See omnystudio.com/listener for privacy information.

Like this episode? Leave a review!

Check out our desert bookstore, buy some podcast merch, or check out our nonprofit mothership, the Desert Advocacy Media Network!

UNCORRECTED TRANSCRIPT

0:00:00 - (Alicia): 90 miles from Needles is brought to you by generous support from people just like you.

0:00:05 - (Chris): You can join Nergs by going to nine 0 mile from Needles.com slash donate.

0:00:25 - (Alicia): You. It's time for 90 miles from Needles, the Desert Protection podcast, with your hosts, Chris Clark and Alicia Pike.

0:00:40 - (Chris): Hey, welcome to 90 MilES from Needles, the Desert Protection Podcast. I'm Chris.

0:00:44 - (Alicia): And I'm Alicia.

0:00:46 - (Chris): And we have the great pleasure today of having as a guest in our studio, the one and only Obi Kaufman, who has a series of California atlases out. The most recent one, which is out in late October, is entitled the Deserts of California, which is just absolutely a delightful book. It's a visual pleasure. It's full of really cool information, stuff I didn't know is in there. I'm just really glad that you were available to talk to us this morning, Obi.

0:01:12 - (Obi): Oh, are you kidding? The pleasure is all mine. I'm such a fan of this podcast. Sitting here with you, too, is a real dream.

0:01:18 - (Alicia): Thank you for joining us.

0:01:19 - (Obi): Oh, yeah.

0:01:20 - (Chris): Give us a little background on the Atlas series. How did it come about?

0:01:23 - (Obi): Yeah, the name of the book is the Deserts of California. Right? Pluralize the deserts. So I can go over these four deserts that we have here, covering about 25% of our state, right. The great Basin to the north and the East. And we've got where we're sitting now, and, of course, in the Mojave or the high desert, and then we got the Sonoran and the Colorado, when Colorado is just really the Sonoran Desert inside of California.

0:01:45 - (Obi): So we've got four deserts, and so it's the deserts of California, a California Field atlas. And I invented the genre, the Field Atlas. Field atlases don't exist, right. And I wanted it to be something between a field guide, but I'm not really concerned with the what of things. If you want a field guide, go get a field guide to discuss, to find, I don't know, the birds of Joshua Tree National park or whatever you want, but it's also not a road atlas. I'm not really concerned about the where of things either, which is funny for a thing, calling itself an atlas.

0:02:16 - (Obi): But what I'm really interested in is the how of things, like how do these big ecological systems interact to form this living network of biodiversity? Really a celebration of biodiversity would be the mission, vision, and values, if you will, of this latest volume. But really, it's at the thrust of all of my work on this political entity called California. Right. So I've got. The deserts of California is the third in a trilogy of sorts called the California Lands Trilogy, as I call it. The first was the forests of California, again pluralizing it. The second was the coasts of California, which is funny to think of as a pluralized thing. It's so funny, in fact, that when I bought the website, thecoastsofCalifornia.com, cost me like $0.25,

0:03:05 - (Obi): nobody saw it to pluralize the coast, but the coasts of Mendocino, much ecologically different in character than like, the coast of San Diego. It's like a completely different know. So breaking that up, describing patterns in California ecology that have been continued to be and will always be, regardless of the urban veneer that we've so effectively erected over the past couple hundred years. Right, so that's the elevator pitch, if you will, about what I do.

0:03:41 - (Alicia): What a cool amalgamation of concepts to create an educational compendium of great size, it sounds like. I'm looking forward to digging in.

0:03:52 - (Obi): Thank you, Alicia. Yeah, it's really. It's a particular attitude. Right. Because my original vocation is a painter. My father was a scientist. Dr. Kaufman's son was going to be a mathematician. So, like, after school and high school, it was calculus homework for me. And so systems thinking, and lo and behold, he makes an artist. So this idea of concilience, that's what Eo Wilson called it in his book about the unity of human knowledge between these great schools of human thought, right? The physical sciences and the humanities. Really, it's almost like the overlap is like a Margin effect. Right? Like the ecotone where you have, you think of where the riparian environment meets the desert environment, you're going to get a lot more biodiversity at that margin. Right?

0:04:37 - (Alicia): Where transition zones.

0:04:39 - (Obi): Exactly. Those liminal spaces. That's right. Where more niche opportunities for resources. There's a metaphor at work there, too, about the nature of knowledge, of understanding. I don't want to make textbooks. Right. I'm not going to leave you alone with the information. This is this and this is this and this is this. I'm really aiming to invite you on this journey of discovery that I'm on to try and figure this stuff out, because it is not simple.

0:05:11 - (Obi): In fact, I love to revel in the complexity. The complexity is where it's at, man. That's where the truth is. When things get too simple, too generalized, we miss so much. And so celebrating that complexity, which seems to be hand in hand with diversity, that's where the vectors of resiliency come from, in a greater understanding of the land and on the land.

0:05:43 - (Chris): Okay, well, that wraps it up. That's a fantastic answer. As we've mentioned before in conversation, I share some life history with you as at least the part about being the person who lives in Oakland and comes to the desert whenever it's physically possible. How long have you been familiarizing yourself with the deserts in California or elsewhere, for that matter? And do you remember your first impression of the.

0:06:06 - (Obi): Oh, that's such a great question. Yeah, I almost interpret that question as, all right, who are you? What the hell do you think you're doing? Because have written this large 600 page book about the deserts of California as if I know a thing. Right.

0:06:23 - (Alicia): Present your desert credibility. Exactly your credentials.

0:06:29 - (Obi): I hope that this book is not like a tourist guide to the desert. I wanted to make this for the desert community. There's 72 maps of the wilderness areas across California. Hand drawn, hand painted maps. Like, who wants that but locals? So I've always been fascinated with the desert's wilderness areas, those roadless, silent spaces. And I spent years and years backpacking at 50 years olD. Now, I don't know how water is heavy, man.

0:07:04 - (Obi): Backpacking the desert is a thing that I did a lot in my youth when I was ready to go after it, and I could. An 85, 90 pound pack is what's always a problem. No matter how majo you think you are, 90 pound pack is no joke. But these days, my backpacking these days is like following contour lines, not crossing them too much.

0:07:24 - (Chris): Yeah, I feel you.

0:07:25 - (Obi): But then I lament that this book in particular, I say things like, I could have drawn these maps with a pair of scissors, right? Which gets to the vague, arbitrary, property oriented geometries imposed on the landscape that have nothing to do with ecology. The political boundaries of these land designations are fences of sorts. If not an actual fence, then they are a political fence to describe an entity that only exists in the collective mind of Sacramento and Washington, DC.

0:08:09 - (Obi): As far as that, there's. But it's a contrivance that we need, isn't it, in order to keep these spaces undeveloped, roadless.

0:08:22 - (Chris): And the boundaries tend to be set by consensus or by who could argue the longest kind of thing. Each of these little arbitrary boundaries, the notches and the bumps and the bulges and the cherry stumps, they all have stories behind how they got that way, which is really fascinating to me.

0:08:38 - (Obi): I don't get too much into that in the book. This isn't A history of Wilderness areas. Right. One of the fun exercises of this book, as I moved through all of these different wilderness areas say, was to identify and pick out two animals and two plants, and different for every single wilderness area in the desert, all 72 of them. But what I want is to give that, then, as an example, demonstrable evidence for the great biodiversity in the desert, to tackle the argument or to tackle the perception, however false, of the desert being empty, when in fact it is full of all of this great speciation locally. And I was able to source all this information on inaturalist, right, which was super fun, very 21st century. I can go into this app and find enough data there to make this analysis and to do that in our artistic context. So it's full of some factoids, this book, the Survey of wilderness area, but not really the political history.

0:09:52 - (Chris): My overall impression just leaving through the deserts of California has been immense gratitude, because, speaking as somebody that used to be a Bay Area environmentalist, the record of Bay Area environmentalists in general dealing with the deserts in California or elsewhere has not been spotless. And there's been a lot of tension in the last 15 years or so about the proper use of the desert landscape. It's often seemed like what one of my colleagues who lives on the east side of the Sierra calls the Sierra curtain, where stuff that goes on to the east of the high peaks gets ignored or denigrated or devalued. We've been having to fight the impression that the desert exists as a place where we put stuff we don't want to live next to, and we extract resources willynilly, even if that resource is.

0:10:35 - (Obi): Space, and with the very false assumption that it's empty space and that is a resource that is economically, there's economic utility there for this thing called the desert to exploit, to exploit events. We also think of the surface of the ocean as, like, a place where we can put our garbage, like, just put it under the surface. The desert operates in that sort of, like, empty thing. If we can't see it, especially as we're driving at 55 miles an hour, or whatever it is, it must not, which is a terribly apt criticism of Sacramento's conservation plan as it dovetails into the carbon zero plan for the state as well.

0:11:25 - (Obi): The desert is doing so much heavy lifting for both of those goals. Okay, right now, the desert is about. It's only 25% of California's overall geography, but it's almost half of the state's 30 by 30 goals. It's about 43%. 30% of California's lands and waters protected for the expressed interest of biodiversity, conservation and preservation. Right. 30% got a lot of criticisms about this program, but I'm not letting great be the enemy of Good.

0:12:05 - (Obi): It's a start. If we do it, and it looks like we are going to do it, make this 30% goal by the year 2030, fingers crossed. We need about a 5 million more acres or so. But if we do it and then we say yay, nature saved, like what a colossal failure that was. No, this is a baseline, but also it's a poor desert here. We've got all of our solar farms, all of our wind farms, all of our geothermal farms. We can make about 7 day to give to the California grid. Okay.

0:12:36 - (Obi): The record for California power usage in one day was like 50. That was just a few years ago. It's some summer day when everybody in California had their air conditioners blasting. Right now the goal is in seven short years for the desert to be able to generate 20 MW. That's almost three times more. That's over 250,000 acres of raised land. R-A-Z-E-D. That's what happens in Earth solar fields. The very important question of spending nature to save nature, that conundrum, I think.

0:13:12 - (Alicia): It really requires us to start reorienting how we view nature, which is how we started this conversation. So when I think about this situation with the desert, old growth desert being put up on the auction block for green energy sources like solar or wind or geothermal, it's a lot like our lungs, our own breathing system. The desert with its old growth is contributing to our clean air. And it's like a pair of lungs. And if you raise, which is the word that was in my mind, if you raise all the cilia from your system, the lungs are going to fail.

0:13:49 - (Alicia): And I feel like that's what we're doing to the surface of the desert. It's just going to keep working and everything's going to be fine. But no, if those little micro hairs that are there just holding everything together and filtering and holding the whole system together, sure, let's try it and see how that works out for us. The dust bowl is a great example of how that went.

0:14:08 - (Chris): I think there's not really a better example of how the rest of California regards the desert than that state 30 by 30 process. At its very root. It doesn't treat the desert as a thing. The desert is split up into regions with other parts of the state. There's a bunch of regions, and there's a bunch of regions that make sense, the Central Valley, the North coast, all that kind of stuff. But the desert isn't treated as one thing, the north part of Death Valley National park is lumped in with the Sierra Nevada.

0:14:40 - (Chris): The southern part of Death Valley is in the inland Deserts region, which also has Joshua Tree and some of Ansa Borrego. But you also have a whole bunch of desert that's in the La region because it's in the Antelope Valley in La County. And same goes for Kern county with the western Mojave. And how do you compose a coherent strategy for managing this collected related set of nested ecosystems? How do you look at the whole desert as a unit if you're splitting it up that way?

0:15:07 - (Chris): And I know there are some people working for the state agencies that are also frustrated with that. It says to me that we're not in the habit of thinking of the deserts as part of California. They're attacked on thing. And so I think the deserts of California, your book, is going to be a really crucial tool for those of us who are trying to spread that sort of awareness of the desert as a thing in California and elsewhere, that deserves its own respect, has an intrinsic right to exist.

0:15:33 - (Chris): And it's not just an adjunct to the resource colony operated by the California coastal cities. It's this thriving place. It's beautiful, and it deserves to have its own destiny preserved.

0:15:46 - (Obi): It's almost like you have these indicator species in different ecosystems. Amphibians are often indicator species of the overall health of the ecosystem in question. Right? It's almost as if the desert itself is an indicator landscape, if you will. It's a litmus test, somehow, of our stewardship writ large. And how the political entities and geographies overlay onto the ecologies of the natural world is something as old as Western settlement itself. One of the last maps in my book is John Wesley Powell's Map of the west, when he rightly said that water and aridity will always define human ecology and human community and human settlement.

0:16:26 - (Obi): And he proposed, as the first director of the United States Geologic Survey, that states should be arranged by major watersheds, which would, for example, if we did that with counties, somehow that would have solved the problem of Los Angeles county creeping over into Antelope Valley. And then you have this hydra of priorities that is unruly at best, disastrous at worst, and how that's going to play out and how we need to rearrange the story we tell ourselves about these political connections. With a county map, it's usually like something from a Spanish land trust and like a creek and a mountain or something like that.

0:17:11 - (Obi): It's that arbitrary. And then it's that old, and it's that anachronistic, too. But I do believe the solution must be democratic, whatever it is. Like, we must hold on to that. When I have friends who are like, I don't even know what democracy is in the 21st century. We hear that all the time, especially in the American context. I get what you're saying, but I'll tell you what democracy is. Democracy is having this conversation right now here.

0:17:36 - (Obi): But it's also when I present my work to the Farmers association in Fresno or whatever, and I'm finding no resistance to it because I'm not coming at them with some sort of political agenda. I'm not running for office. I'm not reinforcing the divisive rhetoric that we're spoon fed every day, because I don't really care about that shit. What I want to do is, how do we solve this democratically? And I know it's very difficult, and I'm simplifying things totally, but we got to start somewhere.

0:18:01 - (Obi): And if we keep coming back to that place where we start, we might get somewhere again.

0:18:05 - (Alicia): Talking ironically, what I'm hearing is that you're really sweeping up some important goody bits, and you're inspiring curiosity.

0:18:14 - (Obi): Okay.

0:18:15 - (Alicia): Trying to motivate. This is a way to look deeper. This is a different way to look at the landscape. And I love the whole field Atlas description in that it's not super focused on education. It's not super focused on culture and history, but it's bringing it together enough so that you can be inspired to be curious yourself.

0:18:33 - (Obi): There you go. I like that a lot. Now, if I could just get a little deep on you all. And I know that you guys aren't afraid to go here in your podcast, but I do have this paranoia. Been thinking about this this week, this paranoia of lost knowledge and even the format of the book as an endangered species of sorts, as reading fades into scrolling, as the thing that people do. And it is horrifying to me that the knowledge of even there's almost like an emergent horizon of literacy itself as a phenomena that comes about the new languages emerging of emoticons or whatever emojis, as we start to get less precise with our semiotics, with the symbols that we're giving each other on a cultural level, how do we so on that if I can just address that paranoia and then transform it somehow, almost like an agenda, I have to not make an argument for something like environmentalism, right.

0:19:57 - (Obi): But rather to tell a common human story of our relation to the more than human world that I think everybody digs.

0:20:06 - (Alicia): This is how it's done. You're doing it. So thank you for tearing the torch to assure your paranoia. There are people out there who feel the same way, Chris and I. Most definitely. Oral tradition is how we've got this mean there is molecular memory that maybe we know about, maybe we don't want to acknowledge, but we're carrying this knowledge with us, and it is our duty to share it with one another. Bravo for taking on such a large job and memorializing it in a book, because that goes one step beyond oral tradition, which we have to maintain, because obviously the great library at Alexandria is an example of. You can write it down, but that can.

0:20:47 - (Obi): Oh, so true. So, well said, Alicia. Yeah, I'm not exactly sure. I'm fascinated by complexity, as I was mentioning before. And the thing that all complex systems share is this. Emergent phenomena. Emergent phenomena always take place regardless of the sort of dancing terrain of variables that we're talking about in any given system. Right? So, as I lament what may be a horizon of literacy, as I just coined it, we also have technology allowing us to enter into casual conversations like this, which this long form podcast conversation, which is, like, counterintuitive to the prevailing zeitgeist, to the prevailing idea that people's attentions are going away when you can listen, some of the most popular media outlets in the world are like hours long conversations about X, Y, or Z.

0:21:45 - (Obi): While it gets back to the old argument that you can really clearly see in my books, and I feel like even with your work here, it's like for every point of despair, there's a point of hope. Like, we can play tennis if you want to, about how things are going to shit or not. And both yes and no.

0:22:04 - (Chris): This has reminded me of an experience I had quite recently. I've been working to stop a water mining project in the middle of the desert. There's a spring called Bonanza Spring, which is an amazing place. More than ten Gallons a minute, 24 7365 coming out of the ground, driest part of the desert. And it's a really culturally important place for local tribes, including the Mojave. And I was out there with a bunch of Mojave people.

0:22:32 - (Alicia): We were working with the Native American Land Conservancy, which a great group. We were just hanging out, talking about the spring, talking about the company that wants to destroy it. And because we had these really nice summer rains, there was a big carpet of cinchweed all over, which is a little mat like daisy family plant with tiny yellow flowers that smells like cumin if you crush the leaves. There were some women a little bit younger than me, maybe in their 50s, late forty s, and they were unfamiliar with the plant. So I was telling them about it and saying, yeah, women used to crush it and rub it behind their ears, around their neck, as perfume, deodorant kind of thing. And as I was saying that, it struck me that here's this knowledge that I happen to have in my hands for a minute that I was handing back to the people who are the rightful owners of it.

0:23:18 - (Chris): I felt all kinds of different ways about that. I eventually ended up just thinking of myself as the spigot that the water flowed through. You don't credit the spigot for the water, but just the idea that knowledge is floating around and the people that really need to have that knowledge sometimes don't. And just the work of sharing what we know about the desert among people that care about it helps in this all hands on deck situation that we have at the moment. We all need to be working on this.

0:23:43 - (Obi): And that's amazing, Chris, because the smell. Smell as a function, a transporter, an agent of human memory, it's something like 3% of our entire genome is dedicated to the lower half of our skull. It's between tasting and smelling things. This is an incredible evolutionary investment. 3% doesn't sound like much, but it's like the entire nervous system is like, less than a half of 1%. It's like an incredible amount of energy we spend in that. And now here I am woefully writing books. I really try to inject this work. There's paintings on every page. It's got to just drip with color and soul. But still, the memory of the cinchweed crushed between the fingertips is so precious.

0:24:25 - (Obi): I'm always, I don't know, tripping over how a book can be more than a book. This Atlas is. It's a very special person that reads these books like cover to cover, because they're not designed to be like that, because I couldn't imagine doing that. But you can't. But they're circular. They can start wherever, because it's geography, it's topography, it's not narrative. And deconstructing that in my own voice, which is my own story, it's funny. My publisher, Heyday books out of Berkeley, they do a lot of native California literature. They also publish news from Native California.

0:25:07 - (Chris): Fantastic magazine.

0:25:08 - (Obi): It's a great magazine, for sure. And it's interesting. Like, when I first had this idea for the California Field Atlas, which was my first book before Forest, Coasts and Deserts back in 2016. I have this idea. I'm going to decolonize all the names. I'm going to research all of the local names, the ancient names, the ancient words for these mountains and these rivers and these watersheds and all of that kind of thing.

0:25:31 - (Obi): And my editor at the time, Lindsay Baer, who herself is a Eastern Shoshone woman, she's. Okay, two things. One, don't do that. She says, you're going to get it wrong. This is very complex stuff that you're suggesting here. And then that's a lifetime of work, and we don't have that time. We got to publish this book. And two, that's not your story. You don't get to tell that story. And that was so liberating.

0:26:00 - (Obi): She's just tell your own story, man. Oh, yeah, okay, I'll own that then. It was this really brilliant sort of restraint on my own expression that freed me was a paradox there, of creativity. Like great restraints make great art. You need those restraints. You need those parameters in order to make the thing, the best thing that it can be and possible at all. And so that was key to finding the trail to making these books.

0:26:32 - (Obi): But, yeah, what reality am I describing as? I have now done this for almost a decade, making book after book, making book every 18 months or so. I'm like, I find that there's four things I like to do in any day, that if I can just whittle my life down to those four things, it's like reading, writing, painting, and walking. And there's almost like this synesthesia, like they all become equivalent as I'm walking through the forest. It's almost like chapters are unfolding. There's a narrative that's becoming evident, or as my eyes are, like, traversing miles of printed ink, there's a journey there as well. I even paint from left to, like, I'm writing.

0:27:17 - (Obi): Handwriting is very important to me, too. There's lots of handwritten calligraphy in that. So what I'm trying to do in my effort to deconstruct the idea of the expert in my own mind, just being. Just trying to find the fullness of my own artistic expression and always trying to be more from here, how do I be more from a place, how do I express my love for it completely, give my life to it? Can I do that?

0:27:48 - (Obi): And what does that look like? It's not like I'm an answer.

0:27:52 - (Alicia): It's not like there's a destination if you find one.

0:27:54 - (Obi): My point is, there's not a destination. Right. The walking itself is the arriving, which is counterintuitive and rather paradoxical also. But it's what we got.

0:28:04 - (Chris): The desert is kind of a moving target, too.

0:28:07 - (Obi): Ain't that the truth. Yeah. What is the desert? Whoa. What is the Mojave? Is it something that's already passed? Recent episodes of this podcast, we've talked about the mourning and the loss of the York fire and the Dome fire, and how those could not have existed as such, were it not for the modern anthropogenic landscape that invasive grasses and atmospheric desiccation say, have influenced on the local ecology. Right.

0:28:43 - (Obi): And the Mojave is already something else than it was 200 years ago.

0:28:47 - (Chris): Yeah, Brendan Cummings makes that point. We've had him on a couple of times and talking about Joshua trees, which he's been campaigning to protect. He says the Joshua tree is adapted to reproduce in a Mojave desert that no longer exists. And that's certainly true of other things besides Joshua trees, black brush and any number of animals. The birds in the Mojave are declining according to the Grenel Resurvey that was done a couple of years ago. It's really a landscape in transition, and I know the Mojave best, but I expect it's also true of the Arizona uplands. A sugar forest, sagebrush in the great Basin and places like that.

0:29:25 - (Chris): These are all moving targets, and you have to place yourself if you want to know which desert you want to address. I think.

0:29:31 - (Obi): I think it's very important to not condemn to death that has not yet died. So again, the future isn't written as such, despite our best evaluations. I think there's something very powerful about the combination of data and love. I have keen memories of the 1980s when I was learning to backpack, say, in Big Sur, when I felt like nature was something that I just missed. There were no elk, there were no whales, there was no beaver, there were no otters, there was no white tailed American kites. And yet all of these species are now rebounding in numbers across the California Floristic province. And that's from this love and data, these conservation efforts, by good policy, good science, effort, work, understanding in a way. So, like, more data, more scientists, more loved this very powerful combination between traditional ecological knowledge, which seems to be resurgenced as well, and scientific innovation.

0:30:34 - (Obi): The solutions in so many ways are still there. Now, I don't want to be like, exhibiting toxic positivity here or whatever. I want to really acknowledge trauma and climate anxiety is real and I feel it every day. It's all I can do to not white knuckle it through that anxiety that riddles and wound but the disposition of my own personality, my own voice is this bottleneck that we're experiencing now, these incredibly complex vector stressor type forces is by definition a bottleneck that opens up onto the other side. And as we used to use the neologism that Wendell Berry calls industrial fundamentalism, right? So as we move through the age of progress with all of its lies of consumerism and predatory capitalism and economic disparity and all of these issues of these justice issues we move through this battle to this new age of resilience is, gosh, it's not only possible, it's probable.

0:31:40 - (Obi): Now, that's saying that with the extinction threat and all of these crises that are mounting like a heap of stones or something we're not going to get crushed or at least transformed, deformed into something else. But the one thing becomes the other thing. And we see that in the geography of the Mojave which itself is a very young thing, really. The modern ecological configuration of this piece of desert land is only 5000 years old really right in line with really the maturation of the incredibly populous successful, sophisticated native cultures and technologies about that time when inside of these modern climate regimes the desert was able to configure itself in a way that was rather homeostatic for several millennia.

0:32:34 - (Obi): And now it's changing again. And the horrifying thing and I think the bewildering thing is that it's happening in human time. It's happening that's almost mirrored in our own bodies as they age and transform into the next thing.

0:32:47 - (Alicia): A scale we can perceive that's something that's comforting about nature is that it's on a scale that we generally can't perceive but we're witnessing something that is happening in real time.

0:32:58 - (Obi): That's right.

0:32:58 - (Alicia): But bringing the data, the science and the love it's a triple threat combination that I advocate for because it's important to know your shit and also know you don't know shit. And it's important to continue to pay attention to those who are going all the way down the rabbit hole for us in the name of knowledge and understanding and then bringing that love which I find it so hard to articulate without sounding new Agey or hippie or whatever but that genuine love for love for source. Not just the earth but the universe that we're swirling around in. It's this whole cosmic soup that we have to have reverence for and bringing love through stewardship and respect and curiosity.

0:33:43 - (Chris): Very rewarding. Difficult conversations to be had, but very rewarding.

0:33:49 - (Obi): It's a tough word, this thing called love. I'm fascinated as far as, like, movements go. One of the big ones for me is the civil rights movement, 60s, or what you have modern thinkers like Cornell west, who offers such wisdom, where he says, never be paralyzed by despair and never be surprised by evil, which is a wonderful call to action and love. I'm not surprised by evil. I'm not surprised by the exploitation of the desert.

0:34:22 - (Obi): It's not shocking to me. Right. And although I may despair, I won't let it freeze my bones. I won't let it because of the fire of love. And then we move towards acceptance. Acceptance.

0:34:39 - (Alicia): Because when we see these cycles happening in nature, for me, I find so much relief. Like the desert, mistletoe is a great example. It'll live in symbiosis with its host tree and not overtake it. But if that host tree has reached the end of its lifespan, or it gets damaged in a storm, or the parasite knows that its host is dying, so it will go full and it'll just take over the entire tree. And I find great comfort when I look at situations that humans find themselves in now, where we're taking over a dying planet. It's almost the same thing, and it's very much so our fault if we want to look at it that way. But it's also very much just the way things work.

0:35:24 - (Alicia): And I don't know if people are remembering, but we're a big part of the animal kingdom. It's in our nature. These patterns exist. And while they may be horrifying, terrifying, and difficult to process, they're natural. And acceptance of that is where I find some peace.

0:35:40 - (Obi): That's beautiful. Symbols of hope on the land for me most recently include Return of the California Condor in numbers. That again, I mean, talk about love and data, which should be the name of an album or something. Okay. Just this week, three more condors were released in Redwood National Forest by Urox. Pregonish is the name for Condors. And in my neck of the woods in the East Bay of Mount Diablo, we have now two dozen Condors have returned to the northern Diablo Ranges, their ancestral territory.

0:36:17 - (Chris): I did not know that. Yeah, it's my old stomping grounds. That's fantastic.

0:36:20 - (Obi): They're here for the first time in 100 years, 150 years. Now there is a story. I have a podcast called Place in purpose with the chairman of the Federated Indians of the Great and Rancheria in Santa Rosa. And his name is Greg Saras, and he wrote a story called the Last Woman from Petaluma. Petaluma is a Sonoma county city, and that's a native word. It's not a Spanish word. Petaluma. And the last woman from Petaluma, who is Greg's great great great grandmother, her name was Supu.

0:36:49 - (Obi): And Supu in 1830 was, upon the last sighting of a Californian condor in the Bay Area, said, how will we dance without featHers? Referring to the regalia that were often decorated of the southern Pomo, decorated with condor feathers. And now that condors are rebounding, it occurs to me that there's no actual word for a flock of condors. You can have a parliament of owls. You can have, what? A flamboyance of flamingos or something like.

0:37:29 - (Alicia): You can have murder of crows, an ostentation of peacocks.

0:37:32 - (Obi): That's a good one. I didn't know that one. That's fantastic. So I recommend, and this was just published on the COVID of the Berkeley Times last week. My suggestion, my humble offering, is that in honor of Subu, we call it a Dance of Condors.

0:37:46 - (Chris): I love it.

0:37:47 - (Alicia): That's beautiful.

0:37:47 - (Chris): That is going into the 90 miles from Needles style book right now.

0:37:54 - (Obi): Very good.

0:37:55 - (Alicia): Dictionary updated.

0:37:58 - (Chris): That's fantastic. Yeah, we actually reprinted that story of Greg's at KCET a few years back.

0:38:03 - (Obi): Oh, very good. Yeah. Having a really good time with the ongoing conversation. Just keeping the conversation going, talking with Greg about what it is to be from anywhere. How do we balance the rights and responsibilities of being in a human community, in a more than human community? How do we talk about these characters who interact with our lives on so many gross and subtle levels, big and small, micro and macro, to get through this bottleneck together, to make sense of something, to use common language, symbols.

0:38:45 - (Obi): It's funny, it's all very specific. Historically, semiotics, as I say, operate within a very specific lexicon of meaning and definition that are very sophisticated. Like a lot of these. A lot of these maps, for example. Map is such a modern phenomenon. The representation is not the thing. You are doing a lot of work figuring out my math. I'm asking you to do a lot of work. And I think there's an appeal there because it becomes a puzzle.

0:39:17 - (Obi): There's a comprehension, there's a delay time that you need to take it in, you need to apprehend it. And if I'm successful at it, it'll only take you a second, because we operate within the same cultural sphere, and doing that finding that is the core of what I'm talking about when I say finding a better story, not making a better argument, it's not me against you. We operate in similar ways towards perhaps a similar goal within a similar ethic.

0:39:52 - (Obi): So that's the promise of the art side of my work.

0:39:58 - (Alicia): It sounds like a very primal stewardship role. That's it, right?

0:40:04 - (Obi): That's right. The human hand, data love. I think we've cracked some new ground here today.

0:40:10 - (Chris): Any prospect of a Nevada Field Atlas series?

0:40:13 - (Obi): No. I've been asked that, like, when are you going to do the field Atlas of Oregon or Texas or whatever? No, I'm from here. And there's something I was even reticent to do. The deserts, because there is something of an original wound, that is that line from Lake Tahoe to the Colorado river, that is the eastern border of California, that bisects the Mojave Desert. There's a contrivance that I perpetuate in this book, and that's difficult for me, although I do have a lot of borderless maps in the book.

0:40:48 - (Obi): But the ecological island that is the California floristic province, everything on the western side of the state, right? So everything on the west side of the Sierra Crest, the transverse and peninsular Ranges, Sienous land. Very good. That is core to my heart. So doing this deserts book has often felt to me like I'm doing a book on another planet. It's another planet out here. But interestingly, especially with the York and the dome fires, the York Fire being the largest fire in California this year, the book that I'm writing now will pairs up with a book that I wrote a couple of years ago called the State of water understanding California's most precious resource. The book I'm writing right now is called the State of Fire, understanding where, how and why California burns.

0:41:36 - (Obi): And that is a puzzle. And so much wrapped up in this story. Wow, what a contentious issue, both popularly, scientifically and internally, working through getting the relationship right with fire, who on a cultural level, on a personal level, I think doing that, whatever that means, is key and essential for solving this bottleneck locally, geographically, as far as the biodiversity crisis is concerned. Right, so that's a whole other podcast.

0:42:19 - (Alicia): So in these days of collapse and fire, what do you do to keep your chin up and get by and enjoy being alive while fighting the good fight?

0:42:29 - (Obi): For me, this is the secret alchemy of beauty. Okay, so this is probably the mystic secret of why I'm not a scientist. I'm not a field researcher. I'm a field researcher, but I'm not a scientist. Science operates with a very specific methodology. I'm a generalist. I'm scavenger. So I operate looking for almost as a nutrient force that my body needs, that some core aspect of my identity requires that I seek out like water in the desert somehow the idea of the beautiful form, the witnessing and that can be witnessing terrible, horrible things, that's certainly the case these days.

0:43:21 - (Obi): But in just the phenomenological universe that the eye of the universe perceiving the thing of the universe and I and the two made one in that rather atonement like thing. That's a lofty answer, the down to earth answer. Because I get asked this question, and I often get asked this question in the sense of what can I do? Often from kids who are almost feeling like this paralytic anxiety feels like I don't even have a future.

0:43:52 - (Obi): The world doesn't end. Nature doesn't work like that, okay? It transforms. It's about recycling of energy. What I need you to do is like, let me ask you this question then. When was the last time you went camping, real camping, go to the river, take your shoes off, go ankle deep and feel that water and breathe deep. Because whatever happens, we're going to need you grounded. We're going to need you unpanicked.

0:44:21 - (Obi): We're going to need you thinking clearly. We're going to need you connected to this place that is injured. But just like the human body exists in this realm of healing as well. And tapping into that power really is the agent of hope, that special vitamin, that particular alchemy that just might tip the scales from something like, as you describe, catastrophic failure towards something that might be like catastrophic success.

0:44:57 - (Obi): What if we could imagine, what if we could imagine, like California's natural world at the end of the 21st century being in better shape than it was at the end of the 20th century, as wounded as it was just 20 years ago. As I was saying, like the end of nature, the end of nature is now canceled. We're inviting in connective ecologies, we're inviting in understanding of corridor based fire ecology, say, or something like that. We're inviting in all of these ancient technologies, sophisticated ancient technologies of how to be from here.

0:45:36 - (Obi): We're going to restore this justice. We are going to look towards solutions because it's the only choice we have.

0:45:48 - (Alicia): That is my favorite answer by.

0:45:50 - (Obi): I thank you both so much for having me here today. It feels so good to be sitting in this corner of Wonder Valley. And talking to you about, gosh, the aspect of the universe that I'm most in love with, this more than human world of California. It's being part of that community is. I wasn't raised with any religion. I don't really know what spirituality is, but I do feel this, if there is one. I think of the infinite relationships of biodiversity across the landscape. It sparks something in me that I would not necessarily hesitate to call spiritual.

0:46:33 - (Obi): I have no idea what that means. And I'm going to be okay with that irrationality. I have to be, because that's part of the complexity and the beauty, the love and the data. Yeah.

0:46:43 - (Alicia): Well, thank you for joining us for these intergalactic explorations.

0:46:47 - (Obi): Intergalactic. I love it. Yes, indeed.

0:46:49 - (Chris): Obi Kaufman, thank you so much for joining us.

0:46:52 - (Obi): Oh, thank you both. Alicia, Chris, you do such great work. I'm so proud to be a part of your community. Now.

0:46:58 - (Chris): Back at you, man.

0:46:59 - (Obi): Right on.

0:47:05 - (Chris): Well, that's it for this episode. Again, thank you for listening to 90 miles from Needles, the Desert Protection podcast. There's a bunch of thanks that we have to give out at the end of this episode, starting with Mr. Obi Kaufman, who was incredibly generous with his time. We also want to thank some people that have donated to the podcast for the first time since our last episode. We have Nancy Klein, Shannon Perry, Kyle Pio, and Elizabeth Thorison, old friend.

0:47:36 - (Chris): Very generous donations from all of them through our givebutter page. And then, of course, on Patreon, Andrew McCuller and Colin. We have so much gratitude for those of you who make this possible. Little heads up. As many of you regular listeners know and those who follow us both on social media know, I am going to be leaving my paid job at the National Parks Conservation association, which has been a great gig, leaving in mid January. And then at the very end of January and the first couple of weeks of February, I am going on the road.

0:48:09 - (Chris): So in approximately this order, I'll be in the Las Vegas and Searchlight, Nevada area, and then down around Aho, Arizona and Oregon, Pipe Cactus National Monument, going from there to the Tohono Autumn Reservation and Tucson, spending a few days in Tucson and then moving from there to, in this order, Carlsbad Caverns National Park, Alpine and Marfa, Big Bend National Park, Albuquerque, Santa Fe, the Four Corners area, including Nahopi and Navajo reservations, Page and Zion, and possibly, depending on road clearance and that kind of thing, the north rim of the Grand Canyon, St. George, of course, and then back into Las Vegas and potentially searchlight.

0:48:54 - (Chris): So if you have ideas for places that might be interested in hearing me blather on about the desert, or if you're working on an issue in your part of the desert that you would love to have featured on the podcast, Let us know. Because this is a decompression from working like a maniac for a couple of decades. So I'm decompressing from that and doing what I can to build the podcast family here. So please get in touch if you have ideas and we really appreciate your support and your listening.

0:49:28 - (Chris): See you next time.

0:51:23 - (Chris): 90 Miles from Needles, is a production of the Desert Advocacy Media Network.